Chapter 7 Author Notes

Plot holes, Labor Disputes, Mark Twain, and Chain Boats

In Chapter 7, the last chance tour gets underway, and we introduce the colonel, who will be the official leader of the expedition to find the tour’s young ladies a husband. From a historical perspective, this chapter stumped me a bit.

I wanted the tour to travel by river from Saint-Denis down to the port of Le Havre. You might be asking me why I did that. Why didn’t they take a train? Even in 1874, it would have only taken three hours to make the trip.

That would have made the most sense, and it is a pretty big plot hole in my book outline. The truth is that the author, me, got carried away thinking about a bit of adventure he wanted to play out on the three-day trip by river barge, and he, me again, didn’t think about it.

If you read the Beta Preview, this issue is still a gaping hole in the believability of the plot, but when you read the final book, I will have added the ultimate French excuse for why the train was out of commission.

A train strike.

If you have ever traveled to France, you may have had to deal with a train strike. It is a constant threat even if it wasn’t happening when you were there. But in the 1870s, was it a thing?

To ensure the excuse worked, I needed to check that labor strikes were happening in the 1870s. Luckily, the French law against labor strikes was changed in 1864, and strikes steadily rose from that point forward. You can read more about the strike ban being lifted here.

Phew, a bullet of my own making dodged. The chapters on the river didn’t need to be rewritten.

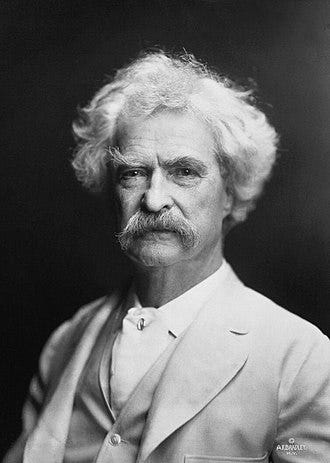

When writing this chapter, the biggest challenge was my assumptions. This lack of knowledge about river travel almost bit me in the butt, but in the end, I was saved by the ghost of Mark Twain.

Because Saint-Denis was an industrial hub in the 1870s, I wanted to have the tour hitch a ride on a barge with some passenger cabins. I went to double-check river travel from Paris to Le Havre and discovered something called a chain boat. My Google skills then failed me, and I could not understand how these chain boats worked, until I read an excerpt from Mark Twain’s travels describing one of the boats in action.

“We ran forward to see the vessel. It proved to be a steamboat—for they had begun to run a steamer up the Neckar, for the first time in May. She was a tug, and one of a very peculiar build and aspect. I had often watched her from the hotel, and wondered how she propelled herself, for apparently she had no propeller or paddles. ....

“As she went grinding and groaning by, we perceived the secret of her moving impulse. She did not drive herself up the river with paddles or propeller, she pulled herself by hauling on a great chain. This chain is laid in the bed of the river and is only fastened at the two ends. It is seventy miles [one hundred and ten kilometers] long. It comes in over the boat's bow, passes around a drum, and is payed out astern. She pulls on that chain, and so drags herself up the river or down it. She has neither bow or stern, strictly speaking, for she has a long-bladed rudder on each end and she never turns around. She uses both rudders all the time, and they are powerful enough to enable her to turn to the right or the left and steer around curves, in spite of the strong resistance of the chain. I would not have believed that that impossible thing could be done; but I saw it done, and therefore I know that there is one impossible thing which can be done. What miracle will man attempt next?” - Mark Twain

When you read my description of a chain boat in Chapter 7, I beseech you, please do not compare it to Mr. Twain’s.

I will leave you with one of his sage quotes that perfectly sums up the conundrum above.

Get your facts first, then you can distort them as you please. - Mark Twain